With reading scores declining for most students across the nation, it’s imperative schools adopt science-based reading methods to ensure more students get the basics they need. With limited funds, how do states/districts tackle the massive endeavor of retraining teachers? Ed Post Managing Editor Mark Lowery recently spoke with education leader Laura Bollman, M.Ed. about a valuable resource educators can use to jumpstart the process.

Bollman is the director of strategy and operations at the Rollins Center for Language & Literacy, Atlanta Speech School. She previously served as president and CEO of the State Charter School Foundation of Georgia as the director of program design and implementation for the CF Foundation in Atlanta. Georgia Trend recently included her in its annual 40 Under 40 list of the state’s best and brightest.

Q&A

Mark: What should teachers, school administrators, etc. be doing to make sure we are equipping as many students as possible in terms of reading instruction?

Laura: I started in the classroom. I’ve worked in education for almost 20 years and I never really connected the dots that reading is not innate. Talking and communicating are biologically innate. We are born to do them. Reading is not, and a reading circuit must be constructed in the brain.

In the most recent centuries and even more now that we’re in the age of information, you have to be literate to have a life of self-determination in America. If you are not literate, data shows that your life across all indicators is going to be a struggle. Without literacy, there is no equity.

Mark: How is the reading circuit in the brain constructed?

Laura: In simplified terms, the reading brain is built with structured literacy in an explicit, systematic diagnostic and cumulative way. Just like building a building, it must start with the smallest components of language to build early literacy skills like letter sound awareness and decoding. Decoding is another word for reading – you are decoding the word with letter sound combinations and you then map those words to your oral language vocabulary and background knowledge – effectively translating print to understanding. Over time, you are more fluent in decoding/reading and skilled reading becomes increasingly automatic.

The simple view of reading says: reading comprehension is the product of decoding and language comprehension. It’s the basis of structured literacy, which is that systematic and explicit approach to teaching reading and writing.

Mark: All that seems to make logical sense. What are we missing in practicality and application?

Laura: We know that only 5% of America’s teachers were taught how to teach reading before they entered the classroom (Ed Week Report, 2019). What they are relying on is curriculums that are aligned to these debunked theories, classroom materials that are aligned to these debunked theories. I want to be very clear, we at Cox Campus – and I certainly, having been a teacher – believe that teachers are the way forward, but teachers must have access to training and expertise that they need to deliver effective reading instruction.

We don’t think that that training should be withheld. We think structured literacy training should be distributed as completely and quickly as possible, which is why we have built the Cox Campus, which is a totally open access platform that is free for everybody.

You can take courses that are accredited, learn, change your practice, modify your practice, deepen your practice. It’s a comprehensive language and literacy learning community.

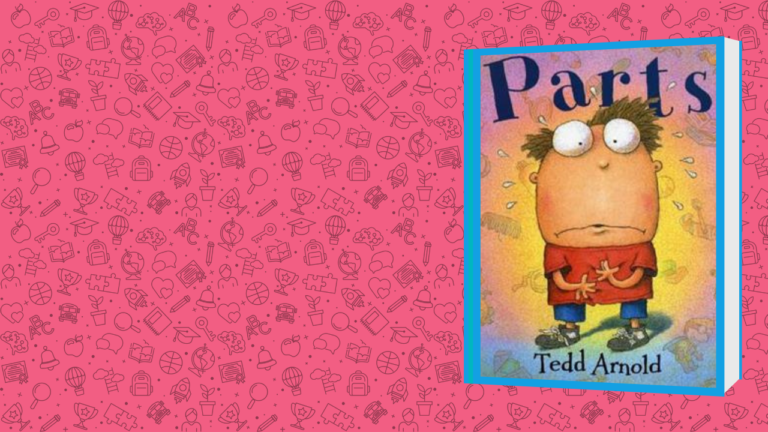

Let me go back to what are we doing now that’s not working. I think that was your question. Largely reading instruction in America is based on debunked theories that hold the notion that reading can happen with exposure. If we put students around books, if we read aloud to students, they will pick up reading. These theories also rely on a lot of reading strategies that don’t include reading/decoding the word. They do include things like use context, use the picture, use predictable text, so you feel like you’re reading because you’re reading something that says the lion sat on the chair, the lamb sat on the chair, the tiger sat on the chair, and you’re looking at the picture and you’re using that predictable pattern.

We’re giving kids these strategies, as opposed to saying we’re going to explicitly and systematically teach how letters build to words, which become increasingly automatic that we map onto our vocabulary and then “aha,” we can comprehend what we are reading.

Mark: This relearning how to teach it, would this also have to go to the college level and how it’s taught to teachers there? Because I would see a difference between training a teacher that hasn’t taught yet and the teacher who’s already been doing it for 10 years, that there’d be different resources to get them to the same place.

Laura: Absolutely. You’re spot on, Mark. We really see the illiteracy crisis and this systemic failure as America’s best kept secret. We know there’s not a single scapegoat, but a systemic continuum here that starts in our pre-service training, extends to our in-service professional development, extends to the core reading programs, instructional materials and assessments that are purchased by our systems of education. The Cox Campus is positioned to push into pre-service training.

Any university can use Cox Campus. Any college of education can use Cox Campus. If you think of it like a free live textbook, you can integrate Cox Campus at no cost into your pre-service training. Certainly we are working to support districts and states to integrate Cox Campus into their in-service training. The Cox Campus also has lesson planning templates, other classroom-ready downloads. In addition to the training that’s going to give you the knowledge you need, we also aim to be very actionable. It’s not just knowledge, but really translating knowledge into practice.

Mark: If I’m a teacher now, I’m a second, third grade teacher, what type of time commitment would be involved in me relearning this skill?

Laura: The science of reading training on Cox Campus, 15 hours of content now, with reading disabilities and multilingual learner content coming in 2023. From early literacy through phonics, how to make read alouds really productive to grow vocabulary and context, reading fluency, vocabulary development, all of the aspects of reading are made free on Cox Campus. I think there is a myth out there that structured literacy is “just add phonics” or “phonics only.” It is totally false. It’s a total myth. Structured literacy is a structured approach to all of the aspects, reading, writing, background knowledge, vocabulary, comprehension, all of the aspects we see in the settled research. All of those aspects in a structured way create a fluent reader, a reader with great comprehension, a skilled deep reader.

Mark: You mentioned earlier that a lot of the curriculum that’s used is based on debunked theories, things that we know are not as effective. [If] I get this training, does my school then have to supplement, get new curriculum to teach it the way it should be taught?

Laura: I think the short answer is probably yes. The reason is because in addition to evidence-based practices, effective literacy instruction works best if you align practices with the structures and systems that support that training. Cox Campus, by making all of that training free, which can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, tens of millions of dollars, by making that free, we are urging, we are hoping that districts, states, and schools strategically reallocate the funding that they will save by training their teachers on Cox Campus so that they can purchase science-based, evidence-based core reading programs, classroom materials – like texts that are aligned with what the kids are learning, and assessments that actually show teachers what literacy skills students are mastering or where they’re struggling in real time.

That’s that diagnostic piece. If we can’t see, if our assessments are too opaque and we can’t see where a child or a group of children is struggling or thriving, it’s going to be very hard to take that systematic approach in an effective way.

In a district or school, the knowledge needs to be there, the practice needs to be there, and those systems and structures that support the practice also need to be there.

Mark: I’m a parent, I’m a teacher, or I’m just a concerned community member and I read this. I’m thinking, oh, we’re saying we’re teaching reading the wrong way. We should be teaching a different way. If we did, we could chip away at this literacy gap in this thing. What action should I be taking?

Laura: Let’s go through those roles, but first I want to say again, we feel very much that teachers are a bit trapped right now. We really put the onus of this crisis on our systems of education.

Our teachers must have what they need and right now they don’t.

As a parent, I think you want to ask your teacher or ask your principal: what does literacy instruction look like? How are you integrating phonics into reading and writing instruction? Are you using the three-cueing method which is associated with those debunked theories? Three cueing is a bunch of strategies like using the picture or guessing at a word, looking at the first letter and taking an educated guess, as opposed to looking at each letter in the word and sounding it out – using your decoding skills.

That is something that a parent can do to start to understand what’s being taught in the classroom, what’s being taught in the school.

If you find that your school, your district is still relying on these debunked theories, I think there are many, many great resources out there. Emily Hanford is doing a lot of work in investigative journalism around this, but there are a lot of resources, including the Cox Campus, that can tell you what reading instruction should look like.

You can start to have those conversations with your district, with your principal.

Mark: And teachers?

Laura: I’ll share an amazing quote, from an educator, a district leader, a state leader, from one of our colleagues in Marietta, Georgia, where they are fully implementing the science of reading across their district.

They’re now in year two of that. It’s the work under a grant called Literacy and Justice for all. The superintendent there said, and I’m sort of paraphrasing, Dr. Rivera said, ‘If your literacy scores are perfect, great, keep doing what you’re doing. But the fact is that is not happening anywhere in the country, and because of that, we knew we needed to make a change.’

If you’re a teacher, look at your district scores. Look at your own classroom scores. If every child in your classroom isn’t reading – then we’ve got to look to instruction because what we know is that every child can learn to read, but they’re not. It’s not because they can’t, it’s because they’re not being effectively taught. I think as a community advocate, it’s probably somewhere between parent and educator. This is going to take all of us to acknowledge that it’s not the kids, it’s not our communities. It is the way that we are teaching reading and we have to be, I think, unapologetically committed to ensuring that every single child learns to read.

Without literacy there’s no equity, there is no justice. This affects every child across every demographic and it disproportionately affects our most disenfranchised communities, children from Black, Brown, lower-income, multilingual communities and it’s not acceptable.